Logistics, Counterinsurgency and the War on Terror: An Interview with Laleh Khalili

George Souvlis: By way of introduction, could you explain what personal experiences strongly influenced you, politically and academically?

Laleh Khalili: I grew up in Iran in the 1970s and early 1980s and being the daughter of Iranian leftist revolutionaries – and later political prisoners and later still exiles – indelibly marked the way I look at the work. On the one hand, growing up in an intellectual leftist household meant introduction to a rich seam of literature and history – not only those of Europeans, but also of Russians and Latin Americans. It meant that names like Che Guevara and George Habash, Angela Davis and the Black Panthers, Ho Chi Minh and General Giap, Salvador Allende and Fidel Castro, Sartre, De Beauvoir, Genet, and Costa Gavras, Garcia Marquez and Cortazar and Neruda, Kazantzakis and Gorky and so many others were familiar and their politics considered familiar.

On the other hand, my parents’ experiences of incarceration and exile and the resultant dislocation, decimation and devastation made me acutely alive to the workings of this form of violence and inevitably wove world-historic events into the fabric of my personal life.

Without these two sets of influences –both intellectual and experiential– I don’t think I would have ever produced the kinds of academic works I eventually produced.

Your first study, Heroes and Martyrs of Palestine, deals with the ways which dispossessed Palestinians have commemorated their past. Could you tell us how about how this has informed the Palestinian nationalist movement? Why it was so crucial? In which ways it influenced the political struggles of the Palestinian people?

I started off by wanting to do some sort of banal doctoral research project on “coping mechanism” of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon or some other such anaemic liberal claptrap. After arriving in the refugee camp that so generously hosted me, it became clear to me that history and memory were resources that were not only instrumentally used by the camp (and local and national) leadership but one which structured the way ordinary refugees told the story of themselves as political subjects. And it seemed to me that these narratives fit within particular narrative genres that were influenced by broader political attachments and structures of the time. When I was conducting my fieldwork, in the early 2000s, Palestinians were in a liminal moment. Oslo’s spectacular failure (so lucidly foretold by Edward Said) was somewhat irrelevant to the refugees in Lebanon who saw the whole process as a kind of betrayal of their right of return. The narrative structure of commemoration was tragic. The prevalent mood of the stories they told, they way my interlocutors framed stories of the past, was of defeat, even if people still celebrated the efficacy of self-sacrifice and the resilience of sumud (or steadfastness). By contrast, in the heady days of the 1960s and 1970s when Palestinian armed struggle had been ascendant, the genre of the commemoration was heroic, and both official and popular narratives celebrated resistance and struggle on and off the battlefield. For me the stark difference had to do not only with the crushing devastation of Palestinian political organizations in the Lebanese civil war but also with a global shift from the era of Third Worldist struggle and solidarity to one in which NGOisation had become the prevalent mode of advancing claims. This global shift from political to a decidedly depoliticizing ethos echoes also in the transformation of the genres of memory from epic to tragic.

In 2010 you co-edited Policing and Prisons in the Middle East. What is the role of prisons in the contemporary Islam, and how has this changed in the era of Neoliberalism? Why has there been such an expansion of the prison system nowadays in Middle East? Does the Foucauldian interpretive scheme about the role of the penal system in West work for the Middle East?

We were really not interested in contemporary Islam. Our contributors all worked on the modern Middle East and what we all really wanted to see was the extent to which the emergence of policing and incarceration were innovations in the region or absorbed and coopted existing forms of domination, discipline and violence. Some of the contributors are of course very much interested in the Foucauldian discussion of discipline, but some of the volume’s contributors were also hesitant about classifying all forms of policing or incarceration as the modern disciplinary or biopolitical form of power. In fact, for us, it was crucial to ground each of the contributions in the very specific spatial and temporal context out of which it arose. As such, the volume includes chapters on French colonial policing in the Syrian desert in the 1920s and 30s; biopolitics of Israeli colonization of Palestine; the police organization in Turkey; policing in Egyptian-governed Gaza of the 1950s and early 1960s; policing spaces of dissent in Jordan; the role of “private” or parastatal actors in the Abu Ghraib prison; the representational and organization value policewomen in Bahrain bestow on the organisation; as well as the extraordinary resistance and self-sacrifice of prisoners in Syria, Iran, and Turkey.

The proliferation of prisons – and especially political prisons – in the Middle East of course reflects the extent to which the task of governing intransigent populations in the region is brutally coercive. The more disciplinary, Foucauldian, reformative penal project is not a familiar sight in the Middle East, but of course that is unsurprising, given that Foucault himself saw the disciplinary prison as an institution specifically grounded in a particular historic context, rather than as a universally generalizable meta-concept (as many Foucauldians have).

In your article “The Location of Palestine in Global Counterinsurgencies” you make the argument that Palestine has been used as a laboratory for counterinsurgency strategies, and has acted as a crucial node of global counterinsurgencies. Why has this been the case? What are the main differences between old and new forms of counterinsurgency? To what extent is counterinsurgency an inseparable aspect of colonial rule?

Palestine is a fascinating –though of course also dispiriting– case because not only was it a temporally and geographically central node in the movement of British colonial policing and pacification practices, doctrines and personnel, but because Palestine continues to remain colonized and subject to an ongoing brutal attempt at pacification by the Israeli state. What makes Palestine particularly interesting is the ways in which the Israeli security apparatuses –including its juridical and administrative bodies– have absorbed British counterinsurgency practices, doctrines, laws and discourses and innovated further. During the Mandatory period, Palestine served as a laboratory in which forms of collective punishment, siege of cities and villages, the building of walls, and the usage of civilians as hostages and human shields, and utilization of laws (for example indefinite administrative detention without trials) was perfected. Some of these tactics were imported from other places where the British were fighting counterinsurgencies, including Ireland and the Northwest Frontier Province. The practices (and the personnel) were then exported to later locales where the British continued to fight against anticolonial forces, including Malaya, Cyprus, and Kenya. Israel has similarly transformed Palestine into a laboratory where it tests not only weaponry (including drones) but also new/old methods of pacification (including caloric control, whereby the amount of food allowed into Gaza is reduced as a form of punishment). These methods and equipment are then exported to other places where states are waging their own wars of counterinsurgency including Indonesia in East Timor and Colombia.

Counterinsurgency can of course be separated from colonial rule including where a state suppresses a rebellious population through liberal or illiberal counterinsurgency measures. The brutal violence of counterinsurgency in Syria is one such example.

However, it seems to me that liberal counterinsurgencies, where the counterinsurgent state professes adherence to law is a twentieth century colonial invention.

Do you think there is a gendered aspect of counterinsurgencies?

I argue that gender works in a variety of ways in counterinsurgencies. My own focus has been on US counterinsurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan. In these places, gender is always already cross-hatched with race, social class and geopolitical/geographic location. So, to give you some examples, at the so called tip of the spear, where counterinsurgency violence is enacted on the bodies of Iraqis and Afghans, Iraqi and Afghan men are effemnisied, Iraq and Afghan private spaces are opened up to the counterinsurgent gaze and coercion, and Iraqi and Afghan prisoners are subjected to sexually humiliating forms of torture. Gender is present there in the horrifying images of Abu Ghraib not only in the sexual torture of Iraqi men, but also in the ways in which US military women –often of working class white backgrounds- are placed in the position of torturer and leash-holder. Gender plays out in narratives of rescue and liberation so often deployed as an alibi for liberal intervention. In the imperial metropoles, a kind of imperial feminism is in operation whereby women involved in counterinsurgency think tanks and government positions try to carve a place in the elite security echelons for women themselves without necessarily adopting the “tough” or masculine personas, without reflecting on their imperial role, and ultimately celebrating their advancement to the driving seat of the machinery of killing as a kind of universal liberatory advance for all women.

In your article “Scholar, Pope, Soldier and Spy” you make strong case about the existence of a dialectical relationship between liberalism and counterinsurgency. Could you explain how these two are connected?

I am not entirely sure that the relationship is dialectical so much as symbiotic. Or at least it is so between the liberal counterinsurgencies of states like the US, Britain and others that profess to adherence to law and administration, and claim (and it is important to emphasise that their claims are often belied by the outcomes) that their methods are softer, more humane, even humanitarian. In the kind of moral claims made by these counterinsurgents –that they act out of virtue, democratic intentions, or attentiveness to human suffering– without ever attending to the consequences of counterinsurgent violence that is of interest to me in that article.

Could you talk a bit about your book Time in the Shadows, and the research behind it?

Time in the Shadows is interested in taking seriously the claim of liberal counterinsurgents that their methods of counterinsurgency are different than those of illiberal regimes. What I mean by this is I aim to understand whether there is a difference between the way a state like the US tries to pacify an intransigent population in Iraq and the way, for example, Russia does in Chechnya. To do so, I look at how carceral methods have come to replace methods of mass slaughter. By carceral methods I mean not only prisoner-of-war camps writ large, but also “black prisons”, extraterritorial forms of incarceration (in islands, offshore or with clients), and the mass incarceration of civilians (which has a long history going back to the concentration camps of Boer War, the Malayan New Villages and Vietnamese Strategic Hamlets to the wall-building that has characterized US counterinsurgency in Baghdad and Israeli offensive pacification measures in Palestine).

I trace the contemporary practices both of the US and the Israelis to colonial precedents exercised by the British and French against anticolonial forces. I do so by showing how the US and Israelis actively learned specific doctrines and practices from the British and the French and the both embodied and discursive conduits of this learning.

The research for the book drew on more than a dozen archives, dozens of interviews with former prisoners and detainees, guards, doctrine writers and the like, and prison memoirs and various other documents.

The other case with which you deal in the aforementioned study in Time In The Shadows is the U. S. war on Terror. Do you think that it signaled a shift of paradigm in terms of the surveillance methods, methods that have since then have been used by the imperialist powers? Do you believe that the war on terror still continues? What has changed the last fifteen years since its launch? Do these shifts go in hand in hand with the wider transformations of the US imperialism?

One of the most significant shifts has been the end of counterinsurgency in Iraq and a kind of retreat of counterinsurgency doctrine altogether and its replacement with counterterrorism discourse, a dependence on drones (instead of soldiers on the ground), and a ramping up of dependence on proxy or client forces both military and political. Twentieth century history of counterinsurgency shows this cyclical swing between the more hands-on and large-scale military intervention counterinsurgents prefer and the more concentrated forms of coercion (delivered whether aerially or though lethal and surveillance-heavy counterterrorism methods) and often through proxies. This toggling between these two forms often happens because of the abject failure of tactics of counterinsurgency, but even more so because of public exhaustion or disillusionment with the unfulfilled promises of counterinsurgency (nation-building being the foremost of these promises). Whether the pendulum swings back depends on the extent to which counterinsurgent forces can insist on the primacy of their methods and persuade politicians and publics of the efficacy of their method and the probity of their promises.

As for shifts in surveillance methods, there are two issues at play here. One is technological innovations; everything from drone surveillance to data-mining to tapping of internet cables all point to technological advances that can affect modalities of surveillance, the kind of data gathered, and the vulnerability of both dissident forces and ordinary publics to state coercion. The second is the extent to which states can persuade the majority of the publics of the necessity of these forms of surveillance because of the threat of terror. What is immensely dispiriting at the moment is to see how brutal terror attacks in European capitals have led to states of emergency, regimes of surveillance and control (both locally and globally), systemic monitoring of suspect populations (like the Prevent programme in the UK and Muslim registries in the US), and a public indifference towards the brutality of these forms of surveillance as long as they are exercised on black and brown bodies. The massive rightward shift in the politics not only of the US and Europe, but worldwide, does not bode well for the vulnerable populations subjected to this politically normalized form of repressive surveillance.

Could you tell us a bit about your current research on shipping and global logistics?

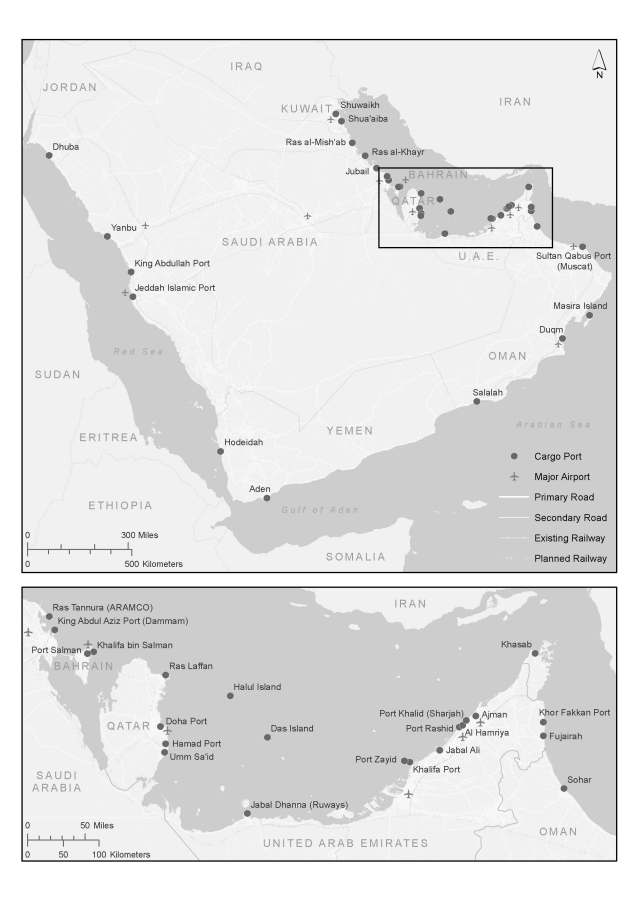

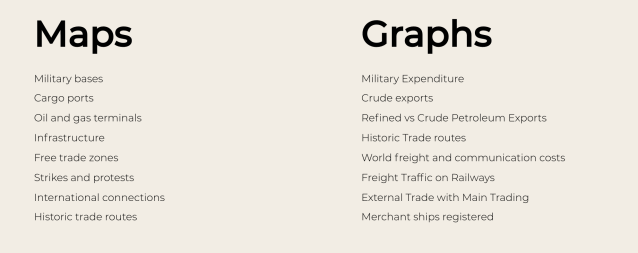

My current research is somewhat different than my previous work in that the familial experiences of incarceration and exile do not directly inform them. That said, there is a direct connection to both previous projects on Palestinian forms of commemoration and on travelling counterinsurgency doctrines. I am at the moment completing the fieldwork and archival research for a large project on the emergence of maritime transport and logistics infrastructures in the Arabian Peninsula. What I am focusing on broadly is the centrality of post-Second World War forms of capitalist production and accumulation, of military logistics, and of struggles around labour and citizenship to the geography and history of modern maritime development. I am looking not only at which ports have risen and which have fallen, but also at the ways in which harbours are made, geological features are transformed into legal and commercial categories, the ecological effects of making of harbours, the spectral persistence of historic trade routes in modern transport corridors and a whole range of other relevant factors. As part of the project I have travelled not only to the ports of the Arabian Peninsula, but also to those metropolitan centres where maritime and trade regulations are made and enforced, where finance and insurance finds a home and where histories of trade are archived. But I have also travelled on contrainerships to various ports in the region in order to get a sense of the way the movement of commodities across space is experienced by the seafarers and dockers who make this movement possible, and also to see the variations in practices and dispositifs of trade across different ports.

In some ways the project draws on my broader research interests. My Palestinian commemoration project was about the ways in which transnational discourses and modes of mobilization influence local imaginaries, while my counterinsurgency project was concerned with the transnational movement of peoples, practices, and doctrines of counterinsurgency across time and space. With my ports and maritime transport project I now look at the movement of physical goods across space. Like both projects, my concern with how violence of colonialism or counterinsurgency is exercised and experienced then translates into trying to understand the power of subaltern resistance to, and enmeshment within, power.

The interview was originally published by Salvage magazine at https://salvage.zone/online-exclusive/logistics-counterinsurgency-and-the-war-on-terror-an-interview-with-laleh-khalili/